MY REDEEMER: A Love Letter to D’Angelo for 25 Years of Voodoo

originally published Jan. 25, 2020

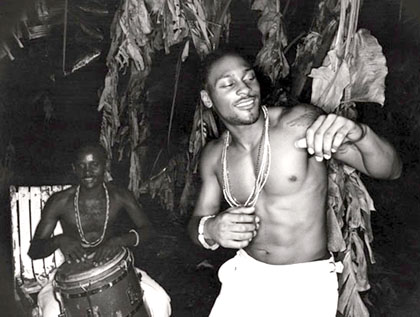

“Voodoo is an ancient African tradition. We use “voodoo” in the drums, or whatever, the cadences and call-outs to our ancestors, and that in itself will invoke spirits. And music has the power to do that, to evoke emotions, evoke spirits.” © D’Angelo to JET Magazine in July 2000

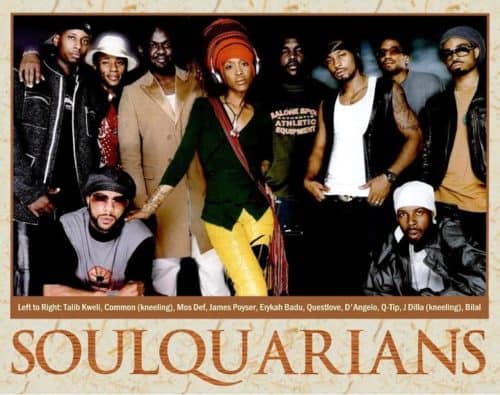

I’m not sure exactly when I first accepted the idea that Voodoo was my favorite record of my lifetime. It just sort of happened, just got its forever hooks into me during D’Angelo’s dozen years in relative hibernation, from 2000-2012. Somewhere along the long, strange trip of the past two decades, this dense, dank, dark, brooding and beautiful slab of sound art became embedded within me. Voodoo remains the one record that I’ve never, ever tired of, offering infinite replay value, and continues to reveal its brilliance. A serenade of the spiritual and sordid, sanctimonious and sexy, it is brimming with bold, obtuse idiosyncrasies, and authored a glorious new chapter in soul music. Two full decades after D & the Soulquarian gang first blessed us up with this monumental masterpiece, Voodoo is a gift that keeps on giving.

I got Voodoo in March of 2000, sixty-ish days after Phish’s massive Big Cypress event, six weeks before my virgin Jazz Fest in New Orleans. Very fertile, vulnerable, and wide-eared moment in time in this boy’s life. I was already conscious that I’d reached a personal apex of sorts with Phish, the proverbial top of that particular mountain, and I was seeking something different in my musical adventuring, something that would deviate far away from my established experiential norms. College homies had rekindled my love affair with hip-hop like The Roots, Wu-Tang Clan, A Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul, Boot Camp Clik. I was 22 and experimenting with Kruder & Dorfmeister, drum & bass, psychedelics & ecstacy. I explored Herbie and the Headhunters, James Brown and Maceo, some Sade, L-Boogie and Badu, and was plundering the Blue Note & Verve rare-groove vaults thanks to the handoff from DJ Greyboy and the Allstars.

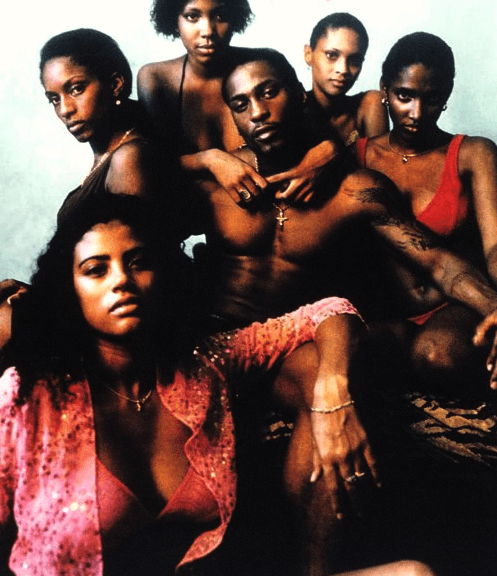

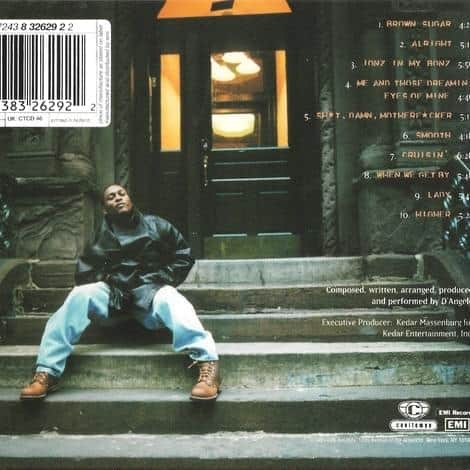

In high school, back in suburban South Jersey, I’d heard D’Angelo’s excellent 1995 debut LP Brown Sugar, but I primarily ignored it. Clearly I was not ready, or yet in touch with that side of myself or the music. Much like Questlove before me, I dismissed the guy as a typical “R&B dude”, a Timbos & cornrows Virginia version of Christopher Williams, Al B. Sure, or at best a Johnny Gill. I only had room for one Bobby Brown in my life, and frankly his ship had sailed once he started hittin’ the base pipe. 90’s R&B, that heavily produced, super-syrupy brand of love songs, just didn’t speak to me at all. I’d naively become conditioned to painting with broad strokes. So I pretty much missed the magic of Brown Sugar in real time, and would only fully realize it’s excellence in retrospect. Voodoo, on the other hand, I would absorb almost immediately, from the rain to the dirt, vine to the wine, and Jah-willing, til the end of time.

It wasn’t until I was a junior in college, the winter of 1999, 272 Pearl Street in Burlington Vermont, snowed in for the twenty-seventh night that winter, that I first got the fever for the D’Angelo flavor. Someone had brought over the DVD Belly, the Hype Williams directed film that stars DMX, Nas, and T-Boz, among others. An unforgettable scene in the hip-hop noir motion picture is soundtracked by D’Angelo’s “Devil’s Pie”, an unorthodox, unclassifiable track produced by DJ Premier of Gang Starr, and prominently found on the soundtrack to the much-maligned cult classic.

“Fuck the Slice, Want the Pie, Why Ask Why, Until We Fry

Watch Us All, Stand In Line, For a Slice of the Devil’s Pie”

As “Devil’s Pie” made the TV speakers pop, immediately I demanded to know what time it was; thankfully, my best bud and fellow music-nerd Jeff was at the crib and he hipped me to the details. This was before online file trading was a thing, and I’d later learn that “Devil’s Pie” was released on Halloween ‘98 as CD/vinyl/cassette promotional single. A young Jedi, I wasn’t that dialed just yet, and initially all I could do was cue up that scene in the movie if I wanted to hear the song. It was vintage Preemo, samples of Teddy Pendergrass, Fat Joe, Raekwon, chopped and cut-up in that patented Premier stabbing cadence

Yet this was different from what I’d come to love from the producer back in those days, there was another element in the recipe for “Devil’s Pie”. I’d already become attuned to D’angelo from his falsetto hook on “Break Up 2 Make Ups” from the second Method Man album, but now my curiosity was piqued even higher, as “Devil’s Pie” reached me instantaneously in a profound manner. Gimme those cracklin’ Preemo drums beneath a woozy, mumbly, sultry serenade, at once sensitive, defiant, and hard as nails. Deal me in.

Over time, a good group of friends developed, with whom I’d study and worship at the Church of D’Angelo for many moons to come. Yet it would again be Jeff who introduced me to the album Voodoo; back in those days, we would lose hours, full days bingeing on music, magazines, messing around on the turntables, making mixes and the like. When we were young, like all close friends, we also talked about sports, girls, and life. Yammering till all hours, a bed of music for a bevy of stories. One evening, over purp bubblers and dark beers on my second story porch, Jeff matter-of-factly regaled me with an unforgettable yarn; in those days he was a bit of a lady killer, a tale of how one night after a college house party he invited a gal back to his crib, and after getting settled comfortably in his bedroom, he put on the new D’Angelo record and left to the kitchen to get glasses of water. When after a few minutes he returned to his room, the first song – “Playa Playa” was well underway, and to his surprise the young woman had already begun to take off her clothes. IT’S LIKE THAT? The next day I marched myself down to Pure Pop – our local independent record spot -and copped my first of several purchased (and dubbed) copies of Voodoo. Rest assured, that little trick didn’t exactly work for me (not for lack of trying thru the years) but alas, a different brand of romance was born, a passion that burns brighter today in 2020 as it ever did on those halcyon Pearl Street nights.

Like so many of us, music possesses my every day – almost every waking moment – to seek, learn, research, understand, and share. It’s precisely why I’ve chosen to devote my life to writing about music culture and associated experiences. As such, I’ve spent twenty years, not just listening to D’Angelo, but studying him. Researching him. Devouring any and all material, articles, videos, and the recent documentary film on a weekly, and sometimes daily basis. I am somewhat obsessed, and I am not afraid to admit it. He’s a once in a lifetime talent, artist and performer. If James Brown was the Father, and Prince the Son, then D’Angelo is the Holy Ghost. He is our R&B Jesus. And Voodoo is his greatest Testimony. Mine too.

Who was/is this guy? The mystique and mystery that surrounds D’Angelo, the making of Voodoo, the Soulquarian collective that created it, the Yodas who inspired them, and the fallout and aftermath of the whole endeavor, they are undeniable components to the majesty and legend of this offering. The entire tale of D’Angelo’s career thus far is pretty intense, somewhat sad, but also inspiring – nothing if not a human story in itself.

After 2000’s resulting world tour, Voodoo won a Grammy for Best R&B Album. D’Angelo retreated from the public eye, and did not go back on the road until 2012, nor release another album until 2014. He was essentially underground, or hibernating, for a dozen years. During that time, he struggled mightily with substance abuse, and wrestled with his former image as a sex-symbol icon of Black music. He was in a serious car accident, was arrested a few times, and put on a lot of weight. His mugshots were punchlines on nighttime TV and morning radio shows around the country. Many people had written him off, or thought he’d thrown it all away. I’m sure on some days, even he thought that of himself. But those of us who were so touched by his art, and most specifically Voodoo, we never gave up on our R&B Jesus. So instead of dwelling on the Behind the Music-type drama that seems to always accompany his story, I prefer to briefly acknowledge it as I have, and place the focus of this essay on how Voodoo came to be, what it means to me, and appropriately celebrate this quintessential, highwater work of art on it’s 20th anniversary.

In the Richmond, Virginia of the 1980’s, Michael D’Angelo Archer grew up away from secular music, and knew nothing of the bright lights and Big Apple of New York City. He was raised by his father in a single-parent household, like most kids who hailed from the backwaters, he began playing music as part of the Penecostal church, initially where his father preached. Fascinated by all the organs and keyboards at the Refugee Temple Assembly of Yahweh Yahoshua the Messiah, at the age of 5, D’Angelo was playing piano in the church band every week, eventually helping to lead the choir.

He continued to perform in various church combinations throughout his youth, but as a teenager he developed an intense preoccupation with all things Prince, he also became drawn to the sounds and ethos of golden-era New York City hip-hop. Richmond is where Mike, as he was known back then, cruised the streets with his homeboys, attempting to holler at girls, trying to score beers, and listening to Roy Ayers or Eric B. & Rakim from the two-tone Dodge they called the “soul van.’ D’Angelo’s grandmother, with whom he was very close and who also was a renowned area preacher, encouraged him to follow his musical gifts and dreams, be it beyond the church or wherever they may take him.

Eventually, after making a name for himself back home, D’Angelo was asked to perform at Amateur Night at Harlem’s legendary Apollo Theater, and he did several times — winning once with a rendition of Johnny Gill’s “Rub You the Right Way”. That success led to a rookie recording contract with EMI, and D’Angelo swiftly made his presence felt with debut LP Brown Sugar, on which he’s credited with pretty much playing every instrument, all the writing, like Stevie Wonder and Prince before him, or so the story goes. He made the demos for his first album in his bedroom, bare-bones on a primitive four-track recorder

Almost immediately, he was celebrated as a breath of fresh air from the stale R&B scene, diverging from the pillowy formulas and homogenized New Jack Swing that first peaked and later decimated the genre. The culture had devolved a long way from Sam Cooke, James Brown, or Marvin Gaye, and D’angelo knew it. Brown Sugar was a tremendous collection of songs, an opening salvo that announced the arrival of a new sheriff in town with a humble, understated authority. But the debut album was merely the tip of his iceberg.

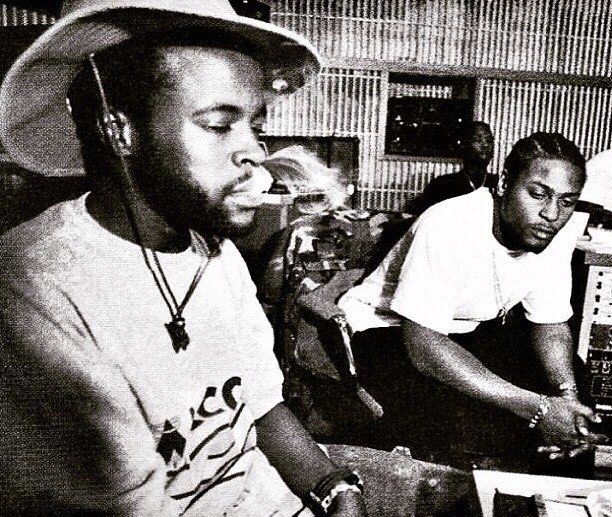

After the quick, overwhelming success of Brown Sugar, D’Angelo retreated from the spotlight and the music industry as a whole. In addition to instant stardom, D battled nearly two years of intense writer’s block, only alleviated by the birth of his first son. He spent time back home in Virginia relatively inactive, it was during this period that he would connect with Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, drummer of The Roots. A seismic, shapeshifting partnership would soon take form in the most appropriately cosmic fashion.

Quest often tells the story of how he first dismissed D’Angelo as more of the same “R&B dude”, but after Brown Sugar dropped like a thunderclap, the drummer “knew he done f*cked up.” Questlove was motivated to work with the singer, and devised himself a plan. He would get D’Angelo’s attention one night while performing “Proceed” with The Roots, doing so by dropping in an obscure drum break from Madhouse (a Prince fusion-jazz side project) that he was certain D’Angelo would recognize. To Quest’s credit, and all of our collective benefit, it worked, as D caught the nod to Madhouse and was vocally quite pleased. The legend of the making of Voodoo was underway.

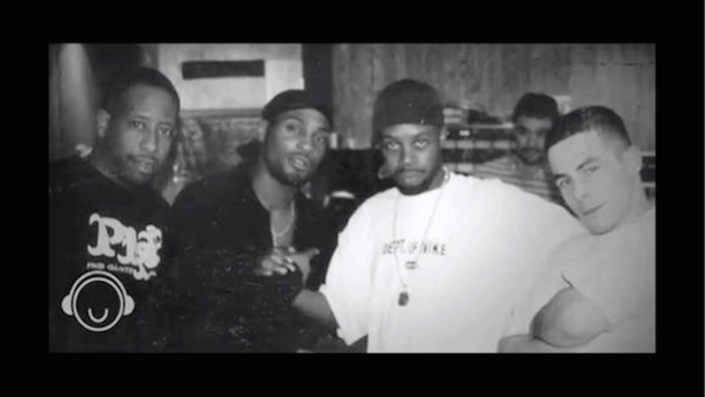

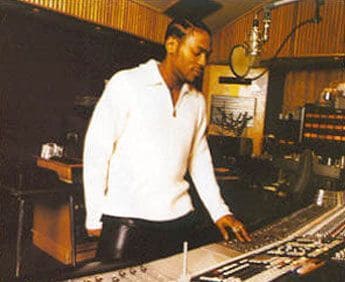

Newly inspired by one another’s fanatical Prince worship, D’Angelo and Questlove hunkered down in the basement of Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios in New York City’s storied Greenwich Village. And they did so for well over three years of intense study and musical spirituality, creativity and community. D had wandered quite far from the Gospel church choir; modern R&B had left him wanting. Meanwhile, Questlove truly believed in his new musical soulmate, telling peers and press that “our savior” had arrived. The drummer was tasked with co-piloting this ambitious project, and bringing it to fruition.

Taken from Saul Williams’ liner notes inside the Voodoo sleeve , a passage so freaking on-point I’ve gone to bed every damn night for twenty-years wishing I’d written it myself. If nothing else, I’ve certainly internalized, adopted and employed the style a time or two:

“We have come in the name of Jimi, Sly, Marvin, Stevie, all artists formerly known as spirits and all spirits formerly known as stars. We have come in the tradition of burning bushes, burning ghettos, burning spliffs, and the ever-burning candles of our bedrooms and silent chambers. We have come bearing instruments and our voices: Falsetto and baritone, percussion and horns. We have come adorned in the apparel of the anointed: leather and feathers, jeans and t-shirts, linen and cashmere, and even polyester. We have come to seduce and serenade the night and the powers of darkness. We speak of darkness, not as ignorance, but as the unknown and the mysterious of the unseen.”

D’Angelo didn’t follow trends on the radio, or do what the record company had expected for his follow up. Instead, at first he didn’t really write or record anything at all. They went to school with it, they turned to the annals of funk, soul, and Black rock greats like James Brown, George Clinton, Al Green, Sly Stone, Jimi Hendrix, Prince, Micheal Jackson, and afrobeat king Fela Kuti. D’Angelo wold immerse himself in a period of devout study and furious jamming. Mining mojo from “The Yodas”, he studied these artists inside and out by watching concert videos and Soul Train episodes on VHS tapes, around the clock study sessions with Questlove and engineer Russell Elevado. Then they’d run to their instruments, the mixing console, and jam out for hours on end.

Elevado revealed himself to be an essential contributor to the Soulquarian sound, first joining up during the final phase of Brown Sugar, he had a major role in the vision and execution of its successor. His calling card was all things analog, the dude is old-school, a dying breed even in 1997. Russell exclusively tracked to two-inch tape. He encouraged D to play a dusty Fender Rhodes at Electric Lady, the same piano on which Stevie Wonder recorded Talking Book. Elevado didn’t hold D’Angelo’s feet to the fire like some producers might, he let him and his collaborators find their way at their pace, and lean into each other, the music, and it’s history. It was that kind of direction and encouragement that empowered D’Angelo and his cohorts to buck the industry establishment and bequeath Voodoo to the world, and with it so much incredible art in its wake. We can thank Russell Elevado for that, and so much more.

The time-consuming and financially-prohibitive process, which never could take place today, saw D & Quest invite a number of like-minded artists over the studio to write, jam and record. D’Angelo and company were set up in the sprawling Studio A, but often times the squad took over Studios B and C depending on what was happening. These sessions all over Electric Lady paved the way for something unprecedented: a fertile creative period that unleashed a prolific run of landmark albums from a loosely-affiliated collective that called itself The Soulquarians. The artists that came together over the course of making Voodoo included Erykah Badu, Raphael Saadiq, Jill Scott, The Roots, Q-Tip, Jay-Dee and Slum Village, Mos Def & Talib Kweli, Bilal, Common, the Welsh bassist Pino Palladino, 8-string guitar wizard Charlie Hunter, late jazz trumpet maestro Roy Hargrove, keyboardist/producer James Poyser, among others. A murderer’s row, if you will.

Albums that were recorded at Electric Lady and released during this four-year studio takeover include The Roots Things Fall Apart, Badu’s Mama’s Gun, Who is Jill Scott?, Bilal’s First Born Second, Common’s Electric Circus, and more. The recording projects were created almost simultaneously and quite often personnel was interchangeable, musical ideas and sonic aesthetics interwoven from one session or artist to the next and back again. The underlying modus operandi was that of a collective creative independence, freedom for a spiritual mission. Everything about this situation ran adjacent, if not counter, to the established commercial-music machinery of the day. When the dust settled, The Soulquarians had masterminded the Neo-Soul revolution, an astounding array of hip-hop and R&B high-art at the turn of the millennium. The crown jewel of this collection would be D’Angelo’s grown n’ sexy Voodoo, released on January 25, 2000.

Ably-assisted by this dazzling assortment of musicians, producers, and Elevado, D’Angelo spent over one thousand days breaking down the established templates of soul and R&B to their core elements, mined the essence of each, and then built a veritable kingdom, by fly-by-night, single-take design. The ambitious, libidinous seance was erected atop two most important, integral pillars: hip-hop and D’Angelo’s church background. In that dichotomy, he sought to walk a tightrope between the sacred and the profane. To remove the machismo and misogyny from hip-hop but keep the rough n’ rugged sonic ethos. Lace the drums with rubber band basslines, beneath a humble, mumbled half-sung dialect affectionately called “D-bonics,” recorded and mixed at a volume noticeably lower than the norm. Eschew established boom-bap production tropes, and utilize the genius vision of a then-still unheralded Jay Dee, aka the late, great J Dilla.

When attempting to reflect on what makes this album so special to the culture, I often declare Voodoo light years ahead of its time. To best identify the elements of Voodoo’s impact, influence and legacy, it’s difficult not to start with the Dilla factor. It permeates the entire journey with a few exceptions, namely “Devil’s Pie” (DJ Premier’s baby), “Untitled” (more on that later). The soothing, throwback soul of “Send it On” also stands out, written and recorded back in Richmond, VA early in the process. In each case, the juxtaposition is definitive, yet the songs don’t feel like outliers in the context of the album.

The Voodoo album credits are long hot topic of much discrepancy among a few contributors, but it’s not my place to speak on who wrote what. However, in spite of what the credits may depict, Jay Dee was a major cog in the wheel as far as manifesting Voodoo’s dirty sonic textures and woozy vibe. Dilla was fond of herky-jerky false starts and is responsible for the “non-quantized” sound of the record. “Quantized” is a technical term for metronome perfection, computerizing the rhythm in time; in D-bonics it means for the beat to be stale, inhuman, and too perfect. The goal during the Voodoo sessions was “to Slum,” as in Slum Village; Jay Dee’s Detroit-based hip-hop group were the first to unveil his “non-quantized” sneakers-in-the-dryer approach to kick-drums and boom-bap on Fantastic Vol.1.

Back in 2000, ?uestlove explained the approach as “the art of totally dragging the feel while being totally quantized…. musically drunk and sober at the same time. It’s also called ‘to Jay that shit.’”

Dilla was also a proponent of back-phrasing, and naturally so was D’Angelo, already an ardent disciple of Jay Dee’s since Dilla laced his “Dreaming Eyes of Mine” remix a couple of years earlier. Back-phrasing was not just uncommon in 90’s R&B, it was unheard of. First, the tempos of contemporary R&B were too fast for anything like that, all of the chart-hopping New Jack Swing flirted with 120 bpms. But D’Angelo was on the slowed n’ throw’d tip, and needed a technician to hold down the bass guitar duties, a guy who could get loose without getting too church with it.

Pino Palladino (John Mayer, The Who) functioned as the sonic anchor to Voodoo’s low-end theoretical design; the virtuoso bassist has been beside (and behind) D’Angelo for everything since. His sturdy, James Jamerson-on-lean basslines rode the “non-quantized” beats in a unique fashion, unveiling a syncopated vibe to the grooves that D liked to call “the grease.” This was essentially the rhythm section’s effort to achieve a looser, behind the beat feel that hangs out in the very back of the pocket, and provides an elastic, or rubber band feeling to the grooves. Cook up the grease, then Jay-that-shit. This specific approach and aesthetic is a definitive element to the fabric, sound, and vision that make up Voodoo as a musical document, a major reason why it’s so revolutionary.

The back-phrasing on Voodoo finds the bass consistently relocating itself, where it lands, and its progression, all in relation to Questlove’s drunk/sober drumming parts. The desired effect that is omnipresent throughout the album manifests in an unsettling, jumpy pulse to the tunes, as if at times the bass guitar is almost out-of-sync. D’Angelo works ethereal Rhodes voicings into the spaces between on these odes to both classic soul and boom-bap minimalism. Questlove only plays proper snare drum on a select few tunes, throughout Voodoo rimshot-flam is king; an effect he dubbed “Mother’s Son” after he lifted it from the Curtis Mayfield song. (Quest credits Bobby Z of The Revolution for the original swaggerjacking.) All of these elements produce a tipsy, blunted feel that leaves lots of room for Roy Hargrove’s inventive horn parts, Charlie Hunter’s chicken-scratch guitar, and of course D’Angelo’s seductive midrange mumbles and reverberating, layered, Gospelized vocal swells.

I could spend another two-thousand words breaking down all of the romance, nuance, musicality, history, homage, course-correction, and leaps into the future found in the DNA of the 13 songs on Voodoo. As I mentioned, there is a cache of thesis-like feature articles that have dissected the album from front to end, here to Mars to Richmond, VA and back again. I spent an inordinate amount of hours, for many years, lurking on The Roots’ Okayplayer forum The Lesson, where venerable musicologists argued and schooled one another about every kind of music you could imagine, but specialized in what we’ve got here. For the better part of a decade – in the message-board era, the merits and shortcomings of Voodoo were discussed ad nauseum among self-appointed professors in The Lesson. Epic battles (Warren Coolidge vs. AFKAP of Darkness vs. Mistermaxxx, anyone?) about whether or not Voodoo deserved to be mentioned in the pantheon of unassailable documents and cultural touchstones like Sly’s There’s A Riot Goin’ On, Marvin’s What’s Goin’ On?, Prince’s Sign of the Times, etc. Scholars would regularly opine dissertations on deeper historical and contextual themes attached to the Black, male R&B singer. Questlove himself (handle: ‘qoolquest’, and then later ‘15’) would chime in every now and again, adding specific names, details, perspective and color to the legend of Voodoo; eventually he posted his Voodoo Tour Diary for us to devour!

So instead of overanalyzing the art pieces – they speak volumes on their own – I will say very little about the songs themselves, as to leave the imagination and explanations to the ears, hearts and minds of each listener. I encourage you to revisit the album with any or all of the aforementioned context, if only to further peel away any layers that may remain between. People will argue, then and now, that Voodoo lacks true songcraft, or that the vocals are indistinguishable at times, that it feels “unfinished”, “unfocused” or “too jammy”. That’s precisely why it appeals to me, and runs concurrent to so much of the status quo. And while they are entitled to their opinion, try telling it to Miles Davis, James Brown, John Coltrane, or any other artist that colored outside the lines, or prioritized the vibe, vision, sounds and textures. D’Angelo did not want to make another polished, radio-ready R&B album, he’d already made one full of those, it’s called Brown Sugar. Dude went in the bunker for what amounted to a presidential term, and made a hard sophomore left with Voodoo. Dug deep within himself, his collaborators, and the annals of funk and soul music, he made uncompromising art for art’s sake, and we’ve been richly rewarded for having faith in his mojo and muse.

Like any timeless record with two decades of replay value, Voodoo is a journey, a ticket to ride on a fantastical voyage to netherworlds unheard, yet familiar. From the very first sounds on “Playa Playa”, an actual recording made at a santeria ceremony in Cuba – the music demands embarkation, the listener is transported to another world for the duration. The ultimate esoteric album opener, it just sucks you right in, lights a stick of nagchampa, a cocktail in one hand and a spliff in the other. “Left and Right” is lots of fun and hella funky, the right amount of flirtatious and provocative; while Method Man and Redman always bring the party, the duo (and their lyrical misogyny) always felt oddly out of place. One can only wonder what might have been if they’d stuck with Q-Tip, a core Souquarian who was reportedly the original feature on “Left & Right”.

The sequencing and overall flow of Voodoo went against the proverbial grain, even for today, but certainly in 2000’s radio/singles driven industry climate. The majority of the tracks clock in at six minutes or more, and nearly all the tempos swimming in a dreamy, opiate-like haze, far below 100 bpms. The resulting feeling on Voodoo is chilled out, unhurried, almost a druggy state of euphoria. It’s undoubtedly an album that takes its sweet ass time. The exception to this particular rule was the frenetic “Spanish Joint”, an uptempo, swingin’ gem of a number that has Charlie Hunter’s unmistakable fingerprints and unique instrumental prowess all over it.

The playful, sauntering funk and greasy throwback groove of “Chicken Grease” pulls back the kitchen curtains, introducing some sunshine to the perpetually lava lamp-lit affair. A tribute to George Clinton and P-Funk, nonetheless they called it “Chicken Grease” because that was a phrase that Prince liked to employ when calling for his guitarist to play minor 9th while playing 16th notes. The throbbing, unrepentant sexuality of “One Mo’Gin”, bass and organ creating an urgent feel beneath D’s pleading come-ons. Torrid and tantric, “The Line” is the ultimate panty-dropper, all things falsetto and the deepest of pocket; while “The Root” is a minimalist lucid dream, again Hunter making his presence felt on the afrodesiac number.

“Greatdayinthamornin-Booty’” is the sleeper cut, a transcendental excursion and Dilla to the core. The lone cover “Feel Like Makin’ Love” (Roberta Flack) reveals a different side of the singer, calling out in a gazillion directions yet expertly woven into the greater fabric of the album itself. The delicate and intricately emotive “Africa” closes the album, with another subtle nod to Prince by using a pattern from “I Wonder U”. “Africa” is simple-yet-oceanic paean to D’Angelo’s young son, co-written with Angie Stone – the boy’s mother ; the intimate letter sends the listener back to the beginning with a familial warmth that never really goes away.

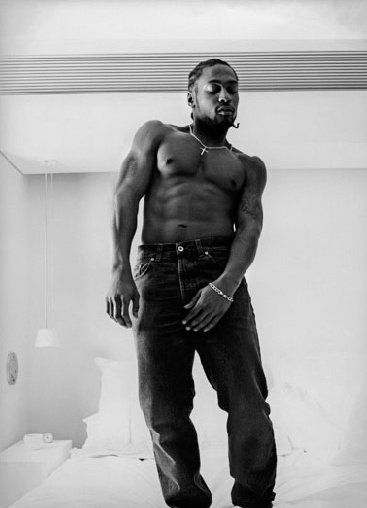

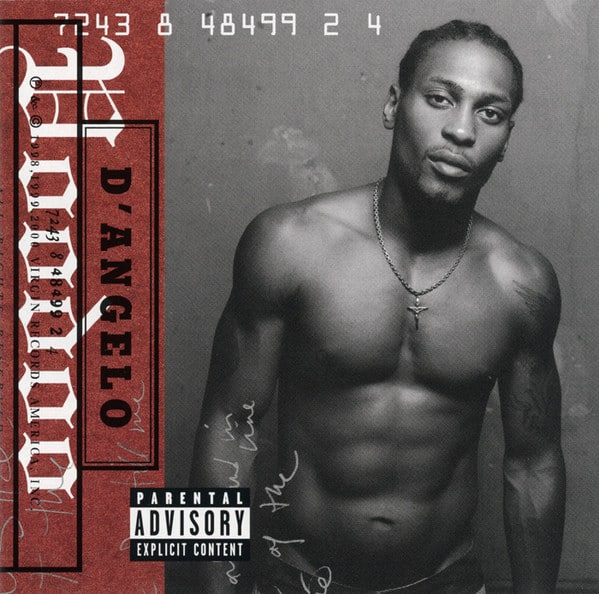

Four-thousand words in, and now, I’m finally going to touch on “Untitled,” albeit briefly. Anyone that remembers how it all went down is likely still a bit saddened by the recollection. And there’s been plenty of feature articles that have explored the effects of “Untitled” on his career, Questlove has spoken on it, his former managers, you name it. Forever the subject of academic papers, feature articles and a bottomless well of on- and offline dialogue, the “Untitled” video has become so iconic in terms of black male sexual representation that it’s virtually impossible to separate the song independently from its visual marketing.

“Untitled” is the one D’Angelo song that most people are familiar with, primarily because of it’s then-controversial, uber-sexy music video, which played every hour on BET and MTV for what felt like a calendar year. The Paul Hunter-directed clip depicted a nearly naked D’Angelo up close and personal, all abs, shoulders and pecs, bathing in gorgeous glow. D croons a falsetto so seductive, sensual and erotic, it likely made Prince himself blush, even if the song (and pushing the sexuality envelope) was a page torn directly from the purple one’s late 80’s book. It doesn’t take a leap of faith to believe the singer might be on the receiving end of fellatio, as he sings through the shimmering piano masterpiece. All anyone ever remembers is the abs, and what they did not see on the screen but cannot get out of their mind. “Untitled” was an incredible piece of art, as was it’s video; but the culture was not mature enough to handle it, and they made him pay for it, dearly.

No matter the stage, the country, or the occasion, women shrieked and screamed for him to “take it off”, and he grew to resent their attention and the song that attracted them to him. As such, I have a hard time listening to “Untitled”, even today, and I avoid the video if I can. It serves as not a reminder of who he was, so much as what might have been, and of course, why it wasn’t. Though the track and it’s video propelled him to superstardom and made him an international sex symbol, looking back, it’s crystal clear that “Untitled” did far more harm than good, and was a saga that marked the beginning of the end of this promising chapter of his career. The soundtrack to everything that he essentially left on the table when he retreated into seclusion. D’Angelo became possessed by an image presented to the world, one that was never really him although he attempted to become it, and when he stepped into that self, it crippled and extinguished him. The ghosts of twelve-pack abs and two-thousand crunches would haunt him in ways we could never understand.

As the video permeated the cultural zeitgeist and the singer was featured in every periodical you could imagine, D’Angelo and his world-class band, named the Soultronics and captained by Questlove, put together an otherworldly three-hour funk & soul revue for the Voodoo World Tour. The enormous ensemble proceeded to tear through theaters and concert halls around the world, leaving them smoldering embers in their wake. Yours truly was lucky to catch one show, in Atlantic City, NJ in August of 2000, and it remains the greatest live music performance I’ve ever seen, hands down. A revelatory, breathtaking force of nature, a whirlwind of sound and fury. But that’s a story, and an essay for another time… (I’ve got six months til the 20th anniversary to get it together.)

But for 22-year old me, it was a tale of a different tape. Voodoo didn’t just give me the keys to the kingdom (it did), the LP was it’s own psychedelic palatial estate. It’s heavenly funk continues to be its own reward. The music – and the musician – pushed me toward seeking a greater appreciation for the struggle of the Black soul singer, Black artists, Black people. I felt almost religiously connected to something that was entirely Black, and not my own, though I loved it so. Yep, it was that potent. Voodoo encouraged me to respect, honor, and give thanks for the contributions of the great creators and innovators who came before D’Angelo. The wonderlands of Marvin, James, Prince, Bob, Jimi, Sly, and the list goes on. Developing an awareness of what they went through, just to give us the music. The songs and sounds that informed D’Angelo, his craft, the Soulquarians’ collective creative process and the resulting, generation-defining piece of art.

Sacred and profane in all the right ways. Voodoo instilled within me a newfound awareness of my masculinity, one that wasn’t rooted in some preconceived tough-guy identity that I saw in the rap videos or sports teams, that a man could be openly sensitive and modestly self-aware, but still look real good doin’ it. Voodoo injected me with the fuel I required to uncover certain parts of myself, and the mojo located in the breast pocket of my Bar Mitzvah suit. It was music that encouraged to step into myself, to become far more comfortable in my own skin than I’d ever been, slowly propelling me to seek more out of my own sexuality. Voodoo took over my body, and moved my spirit in ways that no other art of any kind could, be it on the dancefloor, in the kitchen, the car, the bedroom… wherever.

D’Angelo. He is shaman. His Voodoo remains medicine for good days, bad days, and halfway days. From which it came was Love.

words: B.Getz